Topology

What is it?

Topology is essentially the study of proximity, which is a close analogue for shape. The specifics of how that’s done are not really the point of this post. That’s all for this section.

How is it related to analyzing data?

Most data analysis techniques are already about quantifying some geometric attributes. For instance, when you fit a linear model, you’re really just imposing an affine model on the data, and computing the appropriate parameters (slope and intercept). But these sorts of things work best if you have an idea for what an appropriate shape would be. That’s one area where topology might be able to help. But to hear more about that, you’ll have to wait for my next post.

There is a notion of equivalence (called isomorphism) of topological spaces (bi-continuous bijections). Basically, we consider two topological spaces to be equivalent if one can be continuously transformed into the other and back. That’s actually a very powerful description that captures a lot of non-linearities and things like that. For instance, an egg shape, a sphere, a pyramid, and a tetrahedron are all isomorphic topological spaces, but not a doughnut (torus). And those kinda make sense. But there are some counter-intuitive examples. For instance, if you were to take one of those long clown balloons and tie it up into a poodle, it would also be isomorphic to the bunch above. And, as the joke goes, donuts are isomorphic to coffee cups. I know what you’re thinking. This topology stuff sounds super cool.

So topology would make a wonderful (admittedly incomplete) description of data. But there are some problems: mainly that this whole story breaks down in higher dimensions. Luckily, there is an analogue that can be computed.

Homology

What is it?

Homology is (in an overly-simplified sentence), counting the number of holes. That’s actually a lot more information than you might initially think. It’s actually sufficient to completely classify the space in lower dimensions, and a good approximation in higher ones. Either way, if we knew that info about our data, we’d capture a lot of the non-linear relationships. Either way, it’ll be fun, so let’s get into it.

How to computes…

Triangulation

Simplices

A simplex is a collection of $n$ points with the property that no one point lies in the subspace defined by the other $n-1$ points. The idea is that it’s the minimal number of points with an $n-1$ dimensional convex hull – or, said differently, the minimal number of points to make an $n-1$ dimensional shape. For instance, if we consider $\mathbb{R}^2$ as our ambient space, then the only simplices that exist are 0, 1, or 2 simplices: the 0 simplices being points, 1 simplices being lines and 2 simplices being tetrahedra. If we look at these simplices like building blocks, we can now make something isomorphic to any shape just by glueing a bunch of these simplices together. But we’ll get to that in a bit.

Let $\{v_0,v_1,v_2\}$ be a simplex. Firstly, since it’s a simplex with 3 points, it must be a 2-simplex. And since it’s a simplex, we know that $v_0-v_1\notin span(\{v_1-v_2,v_1+v_2\})$ and the same relationship holds for all the rest of the points. This simplex is supposed to represent any 2 dimensional contiguous ball-like thing. For instance, since a filled-in circle can be continuously transformed into a filled-in triangle (which is, in essence what a 2-simplex is), our simplex becomes a proxy for such circles, and squares, and rhombi, and octagons, but not the Apple logo. But if you take that stem thing and throw it away so you’re only left with the main apple part of the logo, then yeah, that too.

So now if we have any single contiguous $N$-D object without any holes, we can represent it topologically by a triangle. So simplices make the building blocks for general shapes, as we’ll see in a bit.

Simplicial Complexes

So let’s build a simplicial complex! But wait! I haven’t even defined what that is yet! Meh, let’s just roll with it. So given a bunch of things we can represent by simplices (like the full apple logo, for instance), we can construct a simplicial complex to represent it. Some more examples would be: an air-filled balloon (which we’ll consider to be hollow) on a string, a filled water balloon (which we’ll not consider to be hollow) on a string, or a doughnut. The list goes on, obviously, but I think you get the point. We can represent pretty much anything this way.

The specifics really only come in when we try to construct the simplicial complex itself. In order to make the thing have the nice characteristics we’ll use later on, we’ll need to make sure our complexes have some properties. But first, we need to know what the face of a simplex is:

Given a simplex $\{v_0,v_1,…,v_n\}$, a face is the simplex defined by a subset (e.g. $\{v_1,v_2,…,v_n\}$ is a face, and so is the original simplex). If you think of a tetrahedron, for instance, the faces are the four triangular faces we’re used to calling faces as well as the six lines on the edges, and the four individual points. So the faces are kinda similar to our intuitive notion of a face. Now we can define a simplicial complex. A simplicial complex $K$ is a collection of simplices with the following properties (see mathworld):

- Each face of a simplex in $K$ is itself a simplex in $K$

- The intersection of two simplices in $K$ is itself a simplex (hence in $K$)

It’s the second rule that’s really the crux of everything, as we’ll see. But let’s go through some examples…

The Apple logo can be triangulated by two disjoint 2-simplices (along with all the appropriate faces of the two). So we basically forced the first property to hold, and since the two simplices are disjoint the second property trivially holds.

The filled water-balloon on a string can be triangulated by a 3-simplex attached to a 1-simplex along with all the appropriate faces. The filled water-balloon part is clearly the 3-simplex, and the string is the 1-simplex. So let’s prove that the two properties hold. The first one holds trivially, since we defined it as the union of all the faces. The second property holds because if you take any two simplices in this complex, either they intersect at the point on top (a 0-simplex) or they don’t intersect at all! (Pardon the hand waving proof there).

The (hollow) air-filled balloon, on the other hand, is a bit harder to triangulate, but we’ll barrel through it. We can glue four 2-simplices together to be like a hollowed out 3-simplex, then attach a 1-simplex as the string to one of the vertices of the hollow tetrahedron, and we’ll be done. All that’s left is to show the two properties hold. That’s left as an exercise to the reader (ah, the good life).

The doughnut, on the other hand, is a lot more complicated to triangulate. To do that we’d have to specify if we’re talking about the shell of a doughnut or a filled in one. Although this is a fun exercise, the traditional way to triangulate the torus doesn’t have much to do with what we’re going to be using this stuff for, so I’ll take a more data-science type approach to this. If we have a bunch of data arranged in the shape of a torus, we can just take the union of the simplices defined by taking a point and the 3 nearest points to it, and creating the convex hull of those points (or considering them as a 3-simplex).

Associations

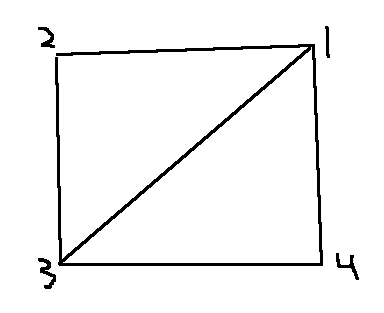

But it would be useful to triangulate the torus using the more traditional approach. To get you started on the right track, you’ll need another tool: association. An association is basically a way of considering things to be equal. It’s kinda like defining specific teleportation or something. I think it’s best to just work out an example. So let’s triangulate some things (like a sphere – the air-filled balloon, for example) but without using the fact that we’re in 3-D space and using associations instead. Let’s start with two 2-simplices joined at one edge (to make something that looks like a square).

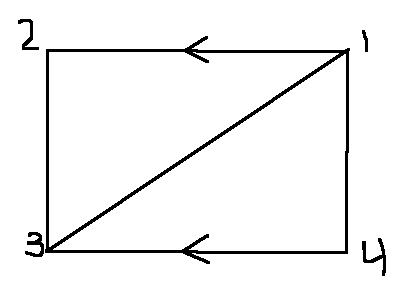

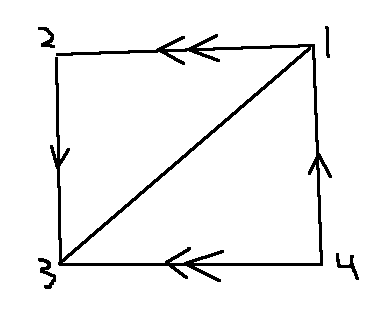

We then make the following association: we say anything along the line $(\langle1\rangle,\langle2\rangle)$ is associated with things on the line $(\langle4\rangle,\langle3\rangle)$ – where order is important. If we want to make it more formal, we could parameterize the line connecting $\langle1\rangle$ to $\langle2\rangle$ by a parameter $t$ such that $f_0(0) = \langle1\rangle$ and $f_0(1) = \langle2\rangle$. We describe this visually like so:

We’re considering all the points on the top line to be associated with (or equal to) their corresponding points on the bottom line. You can imagine this to be kinda like pacman: when you go off the top edge, you come back from the bottom edge in the same direction (because of the association that we’ve made). So, we might as well fold the paper over and tape the two sides together so as to better visualize the association we’ve made. But when we do that, we notice we have a tube!

So the association shown above can be described as a tube. Unfortunately, it’s not a simplicial complex though. This can be seen because if we call the top-left triangle $A$, and the bottom-right one $B$, the intersection of $A$ and $B$ is the diagonal line $(\langle1\rangle,\langle3\rangle)$ and the associated line (it’s only one because the two are associated – hence the same line) $(\langle1\rangle,\langle2\rangle) = (\langle4\rangle,\langle3\rangle)$. So the intersection is two lines, which is a simplicial complex, but not a simplex! So this triangulation doesn’t have the second property that we require all simplicial complexes to have.

We could make it a simplicial complex by dividing the thing into a 9 square grid (so 18 triangles) and then doing the same thing again with the top being associated with the bottom, but it’s a lot to write out. Try it out though. See if you can make it a simplicial complex. If you run into any issues, feel free to email me.

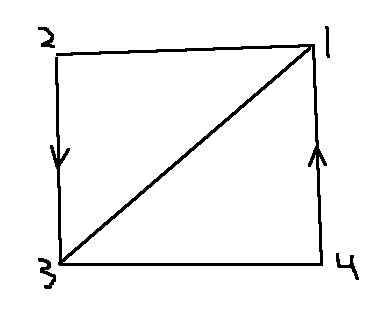

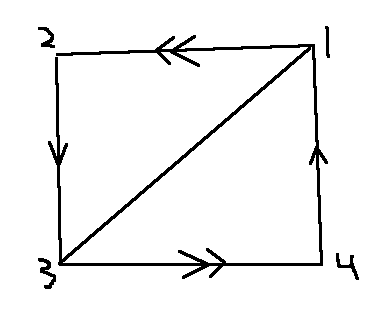

Moving on… Now if we just flipped the association, we get a möbius strip!

It might be useful to actually break out a piece of paper and do this if you’ve never done it before.

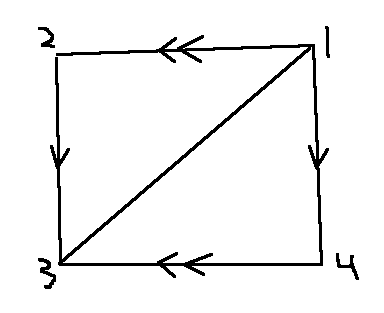

If we take the tube and add this one association it becomes a torus (a hollow doughnut)!

Notice that we identify which sides are connected by the fact that they share the same symbol (the double arrow is connected to the other double arrow, and the single arrow does likewise).

If you’re trying it out on paper, make sure you label the points so you can see them! If you reverse the direction one side of the second association, you get something very different – a Klein bottle!

I feel like it’s probably a bit cruel of me to have put this after the picture, in case you’ve been trying to make the last one with your paper… It turns out, you can’t make the last one in 3D space. You need to either use an extra dimension or tear the paper, unfortunately. But, it’s interesting to see that flipping the association completely changes the thing – kinda like chirality in chemistry.

Like if we take the möbius strip and make the following additional association, you get something called the Projective Plane (\(\mathbb{P}^2\) – also not embeddable in 3D space).

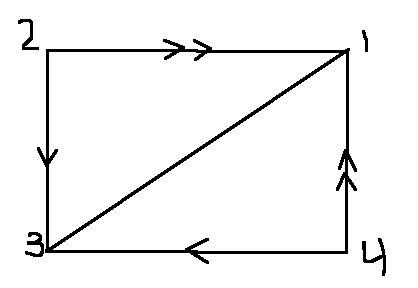

And finally, the following association leads us to a sphere, or, more precisely, the surface of a sphere.

Then, since all the points on the top line (and the bottom, left, and right lines) are all associated, imagine contracting them while keeping the inside of the bag relatively unchanged (as far as area is concerned). So necessarily the bag will puff up like a bubble as the sides squish down to a smaller and smaller hole. Eventually, the edge becomes just a point, and what do we have? Yup, we’ve got a sphere. So that’s one way we can triangulate a sphere.

The problem is that none of these are simplicial complexes. Why not? Can you fix these so that they become simplicial complexes?

Summary

So we’ve triangulated some things, defined what simplices and simplicial complexes are, but we haven’t yet found their utility. For that, just stay tuned! In the next episode we’ll go over Betti Numbers and how to compute them using these simplicial complexes!