Background

Earlier today I asked a colleague what the formal definition of a Unit Factor Portfolio is. He told me “it’s a portfolio with unit exposure to the factor, and orthogonalized to all the others.” That didn’t make sense to me, so I’m going to dig in here.

We (quants) tend to use some form of a risk model to optimize our portfolios1 given a vector of alphas2. This post assumes that you know what a risk model is. Today we’ll be going over risk models from a geometric point of view.

Mathematical Background

Random Variables

A continuous, real valued, random variable3 $X$ can be seen as a vector in $\mathbb{R}^n$, where $n$ is the number of observations you have. So if I take 7 samples of a normally distributed random variable, it might look like this:

>>> import numpy as np

>>> rnd = np.random.RandomState(42)

>>> rnd.normal(size=(7,))

array([ 0.49671415, -0.1382643 , 0.64768854, 1.52302986, -0.23415337,

-0.23413696, 1.57921282])

As you can see, this is just a vector in $\mathbb{R}^7$.

Inner Products

If you’ve spent time in a university’s Math department, you may have heard someone saying, “as long as we have an inner-product4 defined, we have a geometry”. What that means is: if you have an inner product defined, we can define distances and angles using that inner product. Here is how we can define a norm (measure of “size”), distance between two points, and an angle using only inner products (letting $\theta$ be the angle between two vectors $u,v$):

\[\begin{align} \left\| u\right\| =& \sqrt{\langle u, u\rangle} \\ d(x, y) =& \left\| x - y \right\| \\ \cos(\theta) =& \frac{\langle u, v\rangle}{\|u\|\cdot\|v\|} \end{align}\]Covariance

The covariance between two random variables, $X,Y \in \mathbb{R}^n$, is defined as:

\[\begin{align*} \text{cov}(X,Y) =& \sum\limits_{i=0}^{n}(X_i - \mu_X)(Y_i - \mu_Y) \\ =& \langle X-\mu_X, Y - \mu_Y\rangle \end{align*}\]In fact, if we have a covariance matrix defined and we want to compute the covariance between two vectors, the formula changes to $\rho(u,v) = u’Vv$, which is still an inner product as long as $V$ is positive-definite5. In this light, the covariance matrix $V$ is seen as a linear isomorphism $V:\mathbb{R}^n\to\mathbb{R}^n$. Basically, it’s just reshaping the space to more accurately represent the covariance structure we see. $Vv$ is the transformation of $v$ into something that makes a bit more geometric sense than the coordinate structure we started with.

So what does the positive-definite part mean geometrically? Well, that means that all the eigenvalues are positive, but what does that mean? That means that if you look at the vectors before and after transforming them, non of them have completely flipped. This is good, because if one did manage to flip, we’d find that a vector was negatively correlated with itself!

Standard deviation

Since $\sigma_X = \sqrt{\text{cov}(X,X)}$, we already know that the standard deviation of $X$ is just the norm of $X$. So standard deviation is a norm. The two are equivalent. Sweet. Let’s move on.

Correlation

The geometric interpretation of the correlation between two random variables, $X,Y$ is the cosine of the angle between them.

\[\begin{align*} \rho(X,Y) =& \frac{\text{cov}(X,Y)}{\sigma_X\sigma_Y} \\ =& \frac{\langle X,Y\rangle}{\|X\|\cdot \|Y\|} \\ =& \cos(\theta) \end{align*}\]Risk

When we talk about how risky a portfolio is, intuitively you probably understand that as “what’s the probability that I lose all of my money”, and you’re not wrong. That would be what we call downside risk. Unfortunately, that’s not so easy to compute (at least not on paper), and there isn’t much in the way of mathematical research built up on the notion of downside risk. Maybe in a later post, I’ll go over how downside risk relates to the Information Ratio, but not today. There is, however, a lot of research built up on standard deviation, and that’s somewhat related (“how irregular are your returns” is not too bad of a proxy). So we define a portfolio’s risk as the standard deviation of the portfolio’s realized alpha (returns above the benchmark).6

Estimations

Now comes the wonderful task of predicting future risk. This involves estimating a covariance matrix of asset-level returns. But if you’re in the equities world (and even more-so if you’re in the quantitative equities world), the covariance matrix is very large (often on the order of 5,000 by 5,000) and non-stationary7. This means we need a lot of data to fit a good covariance matrix, which means it’s slow to update and will inherently leave out newer assets. Clearly there is a place for a lower dimensional estimator of risk. We call such an estimator a risk model. There are several versions of a risk model, but this is meant to be a short post, so we’ll only go over Barra style factor models.

Factor Risk Models

A factor risk model takes the following form:

\[(Xh)'V(Xh) + D h\]Where $h \in \mathbb{R}^n$ is our holdings (of $n$ many assets) vector, $X \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times n}$ is called our factor exposure matrix (usually shortened to simply, “exposure matrix”), $V \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times m}$ is called our factor covariance matrix, and $D \in \mathbb{R}^{n}$ is the specific risk vector. The exposure matrix is computed using endogenous data (as opposed to modeled data) like the stock’s N-day momentum, the stock’s market cap, number of employees, industry, etc.

If $m \ll n$, the covariance matrix can be computed more efficiently than the full $n\times n$ covariance matrix. This is not a silver bullet, though, as we’ve just segmented our problem into two parts: creating factor exposures and estimating factor risk. There are other types of risk models (such as statistical, shrunken, etc.), but generally they involve the same decomposition: a lower dimensional embedding, then covariance in that lower dimensional space8.

We can look at this style of risk model in a geometric way too. Let’s focus entirely on the first part ($(Xh)’V(Xh)$) for now, and furthermore let’s assume that we’ve fit the model already – meaning we’ve already computed $X$ and $V$ – the factor exposures and covariances.

The first step is to embed $h$ into the lower $m$ dimensional space via $X$. This means the factor model is not – in fact, can not – be a real covariance matrix. It’s rank is at most $m \lt n$ and hence it’s not positive definite. Given that we’re measuring covariance in factor space, the efficacy of the risk model rests heavily on how representative the factor exposures are.

Marginal contribution to risk

One common task is to attribute some amount of the total risk to a particular factor. By that I mean that we have a portfolio and we would like to express the total risk of this portfolio in terms of the risk factors from our risk model. The theory suggests that we want the marginal contribution to risk (MCTR). One way of thinking about this is if we have our factor set $F$, then we would like to first express the risk budget as the idiosyncratic risk plus a linear combination of the factor risks, then the MCTR for a given factor is that factor’s coefficient.

\[\sigma = \sigma_I + \sum\limits_{f\in F}\sigma_ff\]But first, let’s go over a bit of mathematical prerequisites.

Projections

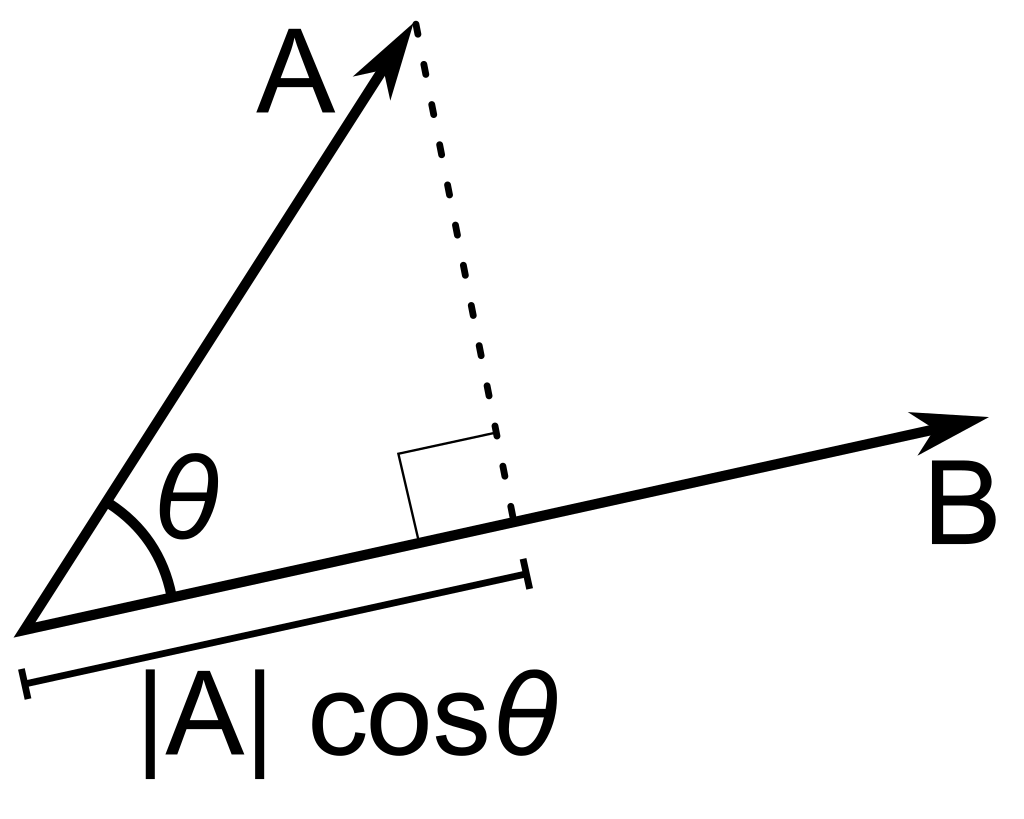

Let $u,v\in\mathbb{R}^n$. Given an inner product $\langle\cdot,\cdot\rangle$ (and the associated norm), the vector projection of $u$ onto $v$ (denoted as $\vec{\text{proj}}_vu$) is defined as:

\[\vec{\text{proj}}_vu := \frac{\langle u, v\rangle}{\|v\|} \frac{v}{\|v\|}\]Another way to see the definition, given our definition of $\cos$ is:

\[\begin{align*} \vec{\text{proj}}_vu =& \frac{\langle u, v\rangle}{\|v\|} \frac{v}{\|v\|} \\\\ =& \frac{\|u\|\langle u, v\rangle}{\|u\|\cdot\|v\|} \frac{v}{\|v\|} \\\\ =& \|u\|\cos(\theta) \frac{v}{\|v\|} \end{align*}\]Geometrically, this gives us the component of $u$ in the $v$ direction. See figure below.

The scaler-projection of $u$ onto $v$ is the coefficient of the vector projection and is denoted as (without the little vector hat):

\[\text{proj}_vu := \frac{\langle u, v\rangle}{\|v\|}\]MCTR

The typical way to define marginal contribution to risk ($MCTR$) is as the partial derivative of the total risk with respect to our factor in question.

\[\begin{align*} MCTR(i) :=& \frac{\partial \sigma}{\partial f_i} \end{align*}\]But if we want to look at this geometrically, we’d ask, what’s the coefficient of this basis vector (factor)? Meaning, what’s $\sigma_f$ for this $\sigma$ in the following formula?

\[\sigma = \sigma_I + \sum\limits_{f\in F}\sigma_ff\]The typical way to do this is via projections. As you may recall from your Linear Algebra course, you find what the projection of $\sigma$ onto a given vector $f_i$ is, and that’s the coefficient you’re looking for. So now we just have to show that this version leads us to the old definition.

\[\begin{align*} \text{proj}_ff_i =& \frac{\langle f, f_i\rangle}{\left\|f\right\|} \\\\ =& \frac{f'Vf_i}{\|f\|} \\\\ =& \frac{(f'V + f'V')f_i}{2\|f\|} \\\\ =& \frac{1}{2\|f\|}\cdot \frac{\partial f'Vf}{\partial f_i} \\\\ =& \frac{1}{2\sqrt{\langle f, f\rangle}}\cdot \frac{\partial \langle f, f\rangle}{\partial f_i} \\\\ =& \frac{\partial \sqrt{\langle f, f\rangle}}{\partial f_i} \\\\ =& \frac{\partial \sigma}{\partial f_i} \\\\ =& MCTR(i) \end{align*}\]So it very literally finds the amount of $\sigma$ that is explained by $f_i$. And it comes with the all the geometric intuition we all know and love.

Extras

Specific risk

So how do we interpret specific risk (what we called $D$) in the factor models? Can we simply add a column to our covariance matrix for specific risk – even if it is mostly zeros? It turns out, no.

One way to see the difference is that the covariance part is a bilinear form, whereas the specific risk is linear. But let’s do a more qualitative investigation (it’s pretty rare for me to look specifically for a qualitative approach, but hey, every now and then…).

We have a surjective map $X:\mathbb{R}^n\to\mathbb{R}^m$ where $m\lt n$, so we know that the dimension of the kernel (the elements that go to 0) is $n - m$. So there is an $m$ dimensional subspace of holdings space that matters – as far as factors are concerned – and $n-m$ dimensions that don’t. We project that parts that do matter into factor space and compute the magnitude of risk there where we know the geometry, and ignore the $m-n$ dimensions that we haven’t modeled by these factors.

If we left it at that, we would have two main problems:

- We’d have a whole bunch of portfolios with reportedly zero risk, and non-zero holdings. This is an unacceptable result that would mean the end of portfolio optimization.

- We’d have a far less accurate risk model.

So we add a vector of asset level offsets, and call it specific risk.

Basically, a risk model is a quadratic form, and the specific risk is the linear term.

UFPs

A Unit Factor Portfolio, sometimes called a Factor Mimicking Portfolio, is the characteristic portfolio with unit exposure to a given factor, and zero exposure to all others9. But what does that mean? Are they correlated? Are the returns correlated?

Given a factor embedding $X$, factor covariance matrix $V$, factor $f_i$, and the associated indicator variable $\mathbb{I}_i$, we’ll get as close as we can to computing a UFP. A UFP is the result of the following Legrangian optimization:

\[UFP_i = \text{argmin}_{h,\lambda}\left( (Xh)'V(Xh) + D h + \lambda (Xh - \mathbb{I}_i)\right)\]Because we know $Xh = \mathbb{I}_i$, we can reduce this down to:

\[\begin{align*} UFP_i =& \text{argmin}\left(\sigma_i + D h\right) \\ =& \text{argmin}\left(D h\right) \end{align*}\]Subject to the restriction that $Xh = \mathbb{I}_i$. Since the kernel of $X$ is non-trivial, we know it doesn’t have a left inverse, so we can’t just left-multiply this whole thing away.

So are the holdings from different UFPs correlated? Almost certainly, but not necessarily predictably so.

Are their returns correlated? If the risk model is any good, neglecting specific risk, the correlation between returns of $UFP_i$ and $UFP_j$ should be close to $V_{i,j}$ – the covariance between the two factors.

Summary

The purpose of this post was to work through some ideas on UFPs, and I think we did that.

-

See Active Portfolio Management by Richard Grinold and Ron Kahn for more information on this optimization. ↩

-

If you let $y$ be the vector of per-period returns of your fund, let $X$ be the vector of benchmark returns (say Market Cap Weighted S&P 500), then the $y = X \beta + \alpha$ regression yields the amount that your fund outperformed the benchmark and the correlation between the two. See my post on linear regression for more info. ↩

-

There are other types of random variables, but we won’t be going into those for this post. ↩

-

If you’re unfamiliar with the term “inner-product”, you can think of it as a more general version of a dot-product or see math-world’s definition. ↩

-

There is an additional requirement that $V$ be Hermitian, but $V$ is real valued, so it’s necessarily Hermitian. ↩

-

Perhaps a better solution would be to consider the standard deviation of the residual of the predicted returns against the realized returns. In practice, the predicted returns tend to be at least an order of magnitude smaller than realized returns, so this is not likely to be immediately fruitful. ↩

-

A non-stationarity distribution is one that changes over time. A lot of non-stationarity means your data from long ago is of an essentially different distribution and is not particularly helpful for estimating covariances. ↩

-

This is not really true with the shrunk (Ledoit-Wolf) covariance matrix, but the same effect is achieved by “shrinking” the covariance matrix to a diagonal one. For more information on that, see Honey, I Shrunk the Sample Covariance Matrix. ↩

-

For more information, see the following bloomberg article. ↩